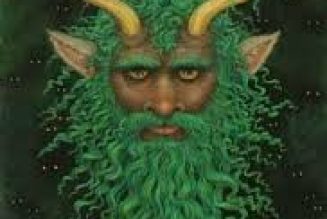

In Irish legend, 12 horned women, all witches, who take over the household of a rich woman and bewitch her and her sleeping family. No reason for the bewitching is given in the story—perhaps, in times past, no reason was necessary, for witches were believed to bewitch simply because they were witches. The legend tells of how the distressed woman breaks the spell. The bewitchment began late one night, as the woman sat up carding wool while her family and servants slept. A knock came on the door, and she asked who was there. A female voice answered, “I am the Witch of the one Horn.” The woman thought it was a neighbor and opened the door. She was greeted by an ugly woman from whose forehead grew a single horn. The witch held a pair of wool carders. She sat down by the fire and began to card wool with great speed. She suddenly paused and said, “Where are the women? they delay too long.” Another knock came on the door. The mistress of the house, who seemed to be under a spell by now, felt compelled to answer it. She was greeted by another witch, who had two horns growing from her forehead, and who carried a spinning wheel. This witch also sat down by the fire and began to spin wool with great speed. The house soon was filled with 12 frightful-looking, horned witches, each one having an additional horn, so that the last witch bore 12 horns on her forehead. They worked furiously on the wool, singing an ancient tune, ignoring the mistress, who was unable to move or call for help. Eventually, one of the witches ordered the mistress to make them a cake, but the woman had no vessel with which to fetch water from the well. The witches told her to take a sieve to the well. She did, but the water ran through the sieve, and she wept. While she was gone, the witches made a cake, using blood drawn from members of the sleeping family in place of water. As she sat weeping by the well, the mistress heard a voice. It was the Spirit of the Well, who told her how to make a paste of clay and moss and cover the sieve, so that it would hold water. It then instructed her to go back to her house from the north and cry out three times, “The mountain of the Fenian women and the sky over it isall on fire.” The mistress did as instructed. The witches shrieked and cried and sped off to the Slivenamon, “the mountains of women,” where they lived. The Spirit of the Well then told the mistress how to break the witches’ spell and prevent them from returning. She took the water in which she had bathed her children’s feet and sprinkled it over the threshold of the house. She took the blood cake, broke it into pieces, and placed them in the mouths of the bewitched sleepers, who were revived. She took the woolen cloth the witches had woven and placed it half in and half out of a padlocked chest. She barred the door with a large crossbeam. The witches returned in a rage at having been deceived. Their fury increased when they discovered that they could not enter the house because of the water, the broken blood cake, and the crossbeam. They flew off into the air, screaming curses against the Spirit of the Well, but they never returned. One of the witches dropped her mantle, which the mistress took and hung up as a reminder of her ordeal. The mantle remained in the family for 500 years. The legend of the horned woman appears to be a blend of pagan and Christian aspects. The well is inhabited by a spirit, a common pagan belief. The horns of the witches symbolize the maternal and nurturing aspect of the Goddess, who is sometimes represented by a cow. The horns also symbolize the crescent moon, another Goddess symbol. In ancient Greek and Babylonian art, the Mother Goddess often is depicted wearing a headdress of little horns. Yet the horned women of the legend are not maternal and nurturing but hags who cast an evil spell, fly through the air, and shriek curses—the portrayal of witches spread by the Church. The cardinal point of the north is associated with power, darkness and mystery in paganism, but in Christian lore it is associated with the Devil.

Horned Women

908 views