Gods

The Old Gods

Know that the Gods need our worship, even as we need food and drink. Do not think that they serve us, for we are the servants. Therefore do not bargain or demand through prayer or ritual. The Gods sha...

A God/Goddess Spell

You will need the following items for this spell: Your voice and alone timeSay this 4x Gods and Goddesses hear my pleaits my greatest wish so i hope to beA god of nature,life and furyBlood and war may...

God/Goddess Spell’

You will need the following items for this spell: Your voice and alone timeSay this 4x Gods and Goddesses hear my pleaits my greatest wish so i hope to beA god of nature,life and furyBlood and war may...

Cernunnos

Cernunnos is a Celtic god associated with nature, fertility, animals, and the wild. The name “Cernunnos” is derived from a combination of the Celtic words “cern” (meaning horn)...

Gods, Fae, Elves, and Ancestors: Are They All the Same?

Gods. Fairies. Elves. Ancestors. The deeper we go into our pagan history, the more we see a blurring of the lines between the spirits. In fact, many of the sagas, legends, and lore point to the idea t...

Abcán

In Irish mythology, Abcán (modern spelling: Abhcán) was the dwarf poet and musician of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the early Celtic divinities of Ireland. He was said to have a bronze boat with a tin sail.[...

Belinus

The old Celtic name for May Day is Beltane (in its most popular Anglicized form), which is derived from the Irish Gaelic ‘Bealtaine’ or the Scottish Gaelic ‘Bealtuinn’, meaning...

THERION

THERION: Literally, the wild, the life-force within us, the animal powers. Ancient Greek name equated with the Horned Gods whose power is in the phallus.

RA-HOOR-KHUIT

RA-HOOR-KHUIT: the Child of Hadit and Nuit, the event-act, the now. A title of Ancient Egyptian god Horus as the Enterer; literally meaning – The crowned and conquering child.

HADIT

HADIT: (Had-de) The infinitely small atomic point, the bindu. A Thelemic god, but considered the complement to Nuit. He is the infinitely small point and heart of every star.

Baldur

Baldur (pronounced “BALD-er;” Old Norse Baldr, Old English and Old High German Balder) is one of the Aesir gods. He’s the son of Odin and Frigg, the husband of the obscure goddess Nanna, and the fathe...

Bacchus

Who Is Bacchus? Bacchus was essentially a copy of the Greek god Dionysus. He was the god of agriculture and wine and the son of Jupiter (Zeus in Greek mythology). He wandered the earth, showing people...

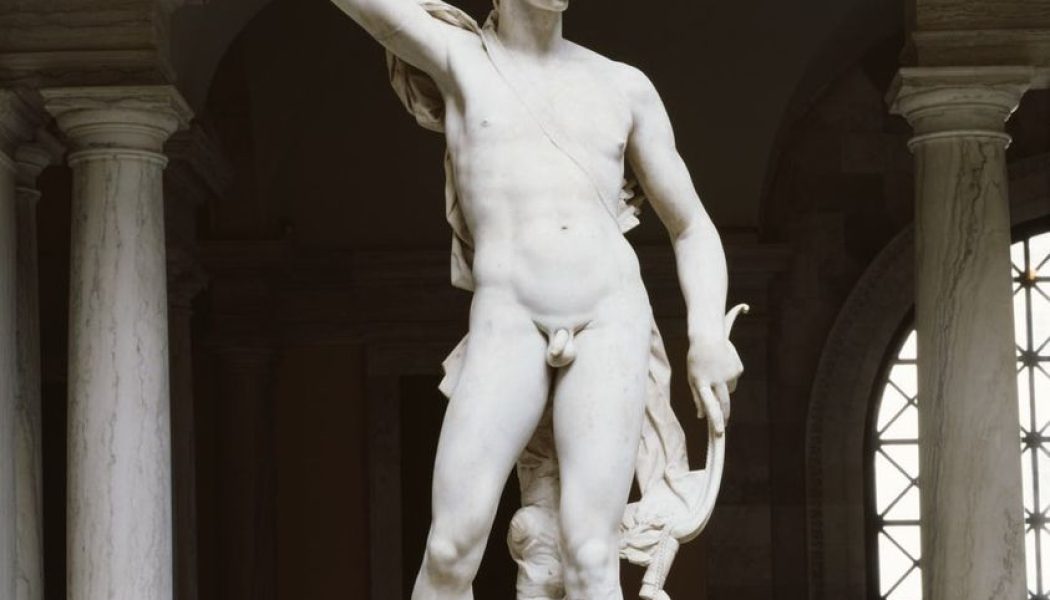

Apollo

Young and lusty, the patron of doctors and occasionally the bringer of pestilential death, enlightened Apollo inspired prophecy, music, poetry, and the civilized arts, and was the ultimate embodiment ...

Aker

Aker is an earth god who also presided over the western and eastern boarders of the Underworld. In early representations, Aker is shown as a narrow strip of land with a human or lion head at both ends...

A Witch’s God

The witch’s God has been denied! In His many masks He has been debased, despised, and relegated to a power of evil by a subjective regime that reviles passion and individuality. You see, our God’s pre...

Lammas: Honoring the God Lugh

If your celebrations focus more on the god Lugh, observe the Sabbat from an artisan’s point of view. Place symbols of your craft or skill on the altar—a notebook, your special paints for artists, a pe...