Witches

Swamp Witch

I’ grew up In New Orleans, In tbe swamps and Is safe to say that I’m a Swamp Witch.I know what you’re thinking, what in the name of Gaia is a Swamp Witch? Well, it is actually fairly self-...

New Witches Guide

Becoming a witch is a personal journey and occasionally a solitary one, despite what you may hear other witches saying there is no one way to go about becoming one. It is however important to learn wh...

Slavic Witch

To be a Slavic witch, one possess the ability to astral travel and fall easily in and out of trance states. Furthermore, Slavic witches observe three major taboos during ritual; nudity, silence, and n...

Rosaleen Norton: The Life and Art of Australia’s Infamous Witch

Rosaleen Norton was an Australian artist and occultist who gained notoriety in the 1950s for her controversial and provocative artwork. Born in 1917 in Dunedin, New Zealand, Norton moved to Sydney, Au...

Malin Matsdotter: Who Was She and Why Was She Important?

Malin Matsdotter was a woman who lived in Sweden during the 17th century. She is known for her involvement in a high-profile court case that attracted attention throughout the country. The case centre...

The Witch of Endor: Biblical Account and Historical Context

The Witch of Endor is a biblical figure from the Old Testament. She is mentioned in the First Book of Samuel, chapter 28, and is known for her role in summoning the spirit of the deceased prophet Samu...

Robert Cochrane Witch: The Life and Legacy of a Pivotal Figure in Modern Witchcraft

Robert Cochrane was a significant figure in the revival of witchcraft in Britain during the 1950s and 60s. He was born in 1931 and grew up in London. Cochrane was a practitioner of traditional witchcr...

Patricia Crowther: A Brief Biography

Patricia Crowther is a well-known name in the world of Wicca and witchcraft. She is a British author and practitioner of the craft who has been active since the 1960s. Crowther is widely recognised as...

Clutterbuck, Old Dorothy (1880–1951)

The high priestess of a coven of hereditary Witches in the New Forest of England, who initiated Gerald Gardner into Witchcraft in 1939. Little was known about Clutterbuck for many years, prompting som...

CROWLEY, ALEISTER: An Opinion from Doreen Valiente

Aleister Crowley earns a place in witchcraft, not because he was a witch, but because he was not ! This, of course, does not stop Crowley’s name being dragged into every Sunday newspaper’s latest “Exp...

Alex Sanders. A Magic Childhood

Left to himself, Alex might have ended his foray into witchcraft there and then, but family circumstances forced him into contact with his grandmother almost daily and before long he found himself bec...

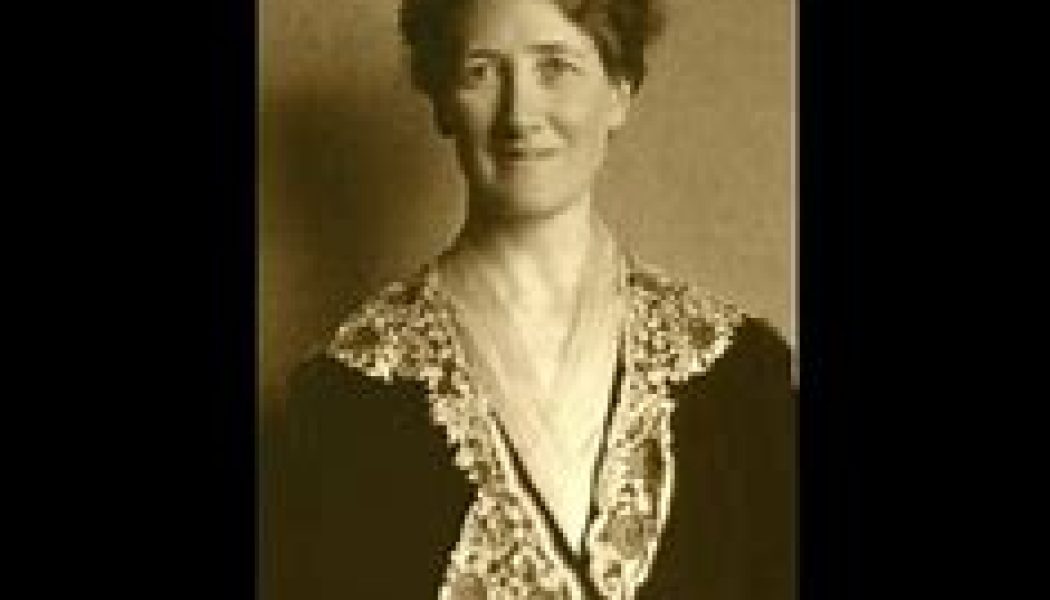

Margaret Murray (1863 – 1963) Part Two

Murray, seeing parallels with her Egyptology work, started digging through documents, and in 1917 she published “Organizations of Witches in Great Britain” in the Folklore Journal. That dry-sound...

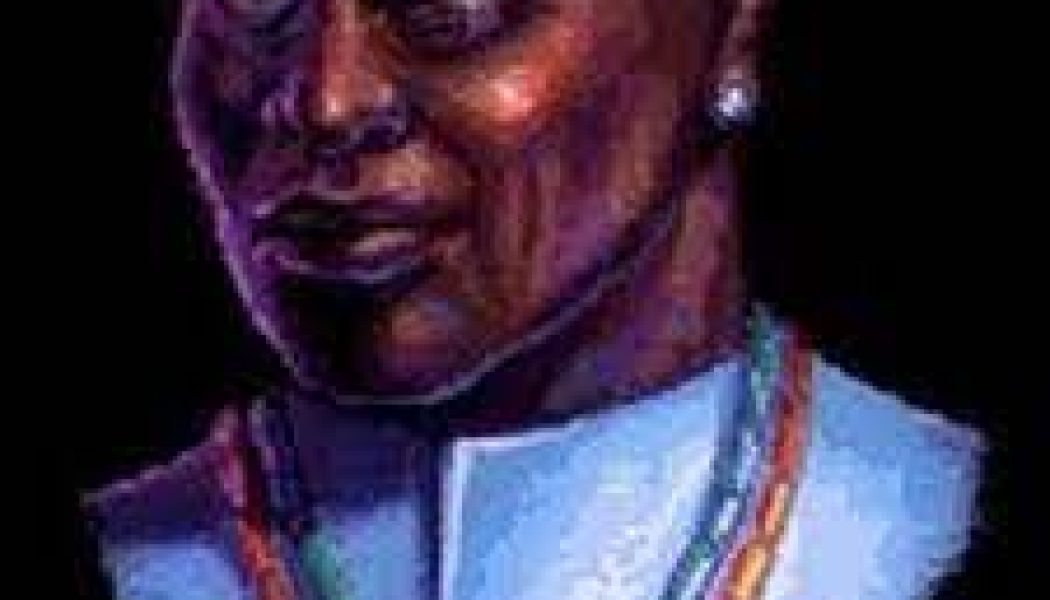

Doctor John (19th century)

Famous American witch doctor, Doctor John (also called Bayou John and Jean Montaigne) was a free black man who owned slaves in antebellum New Orleans. A huge man, Doctor John claimed he was a prince i...

Alex Sanders- The Haunted Hill

In 1939 David was born, the sixth and last of Alex’s brothers and sisters, and soon afterward war broke out. Alex, with most of the other children in Manchester, was evacuated to the country to escape...

Margaret Murray (1863 – 1963) Part One

Margaret Murray was noted Egyptologist, archaeologist, anthropologist, folklorist, and first-wave feminist, she is now best-known for a series of books on witchcraft that profoundly shaped the modern ...

Hohman, John George (d. ca. 1845)

Hohman, John George. The most famous braucher in the powwowing tradition of folk magic, spells, hexes and healing. John George Hohman was a German immigrant to America and the author of the widely cir...

Alex Sanders – Calling Down the Spirits

When Alex was seventeen he met a girl who was a keen spiritualist. Learning of his interest in the occult she invited him to a meeting. He was curious to see if it had anything in common with witchcra...

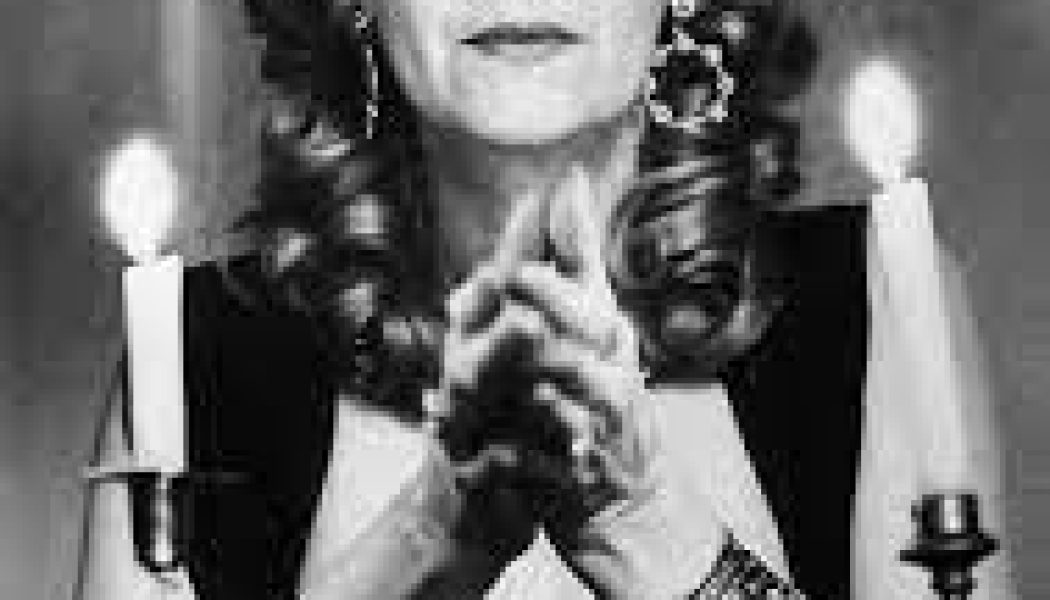

Duncan, Helen (1898–1956)

Duncan, Helen (1898–1956) British Spiritualist whose conviction on flimsy charges of witchcraft led to the repeal of Britain’s Witchcraft Act of 1736, thus clearing the way for the public practice of ...

Alex Sanders – The Young Initiate

There was nothing about the day to suggest it would change the course of his life and influence him until the day he died. It was grey and cheerless, like many other days in Manchester, and Alex was a...

Biddy Early (1798–1874)

Irish seer and healer often described as a witch. Most of what is known about Biddy Early has been collected from oral tradition, and many of the stories about her have numerous variations. Nonetheles...

- 1

- 2